A New Kind Of “Free To Play”

Sept. 18, 2024

Can web versions create a fairer game economy?

Once the app stores added the ability to have in-app purchases, the “Free To Play” (F2P) model became the dominate financial model for mobile games.

Wikipedia says:

Free-to-play (F2P or FtP) video games are games that give players access to a significant portion of their content without paying or do not require paying to continue playing … The most common is based on the freemium software model, in which users are granted access to a fully functional game but are incentivised to pay micro-transactions to access additional content or more powerful in-game assets. Sometimes the content is entirely blocked without payment; other times it requires immense time ‘unlocking’ it for non-paying players, and paying the fee speeds the unlocking process.

The issue with F2P is that only a small percentage of players will actually buy anything. Estimates are as low as 2% of players will do this.

From: How to Make a Mobile Game That’s Profitable

On average, only 2–5% of players pay in a f2p game

Unfortunately in some games this has resulted in a “Skinner Box” like experience where games are designed to extract as much payments by creating an addictive experience for players who have an obsessive compulsive nature.

The Skinner box is a chamber that isolates the subject from the external environment and has a behavior indicator such as a lever or a button.

When the animal pushes the button or lever, the box is able to deliver a positive reinforcement of the behavior (such as food)

Partial reinforcement occurs when reinforcement is only given under particular circumstances. For example, a pellet or shock may only be dispensed after a pigeon has pressed a lever a certain number of times.

There’s also the obvious “pay to win” model, where in-app purchases make it easier to ‘beat’ an opponent, but the “Skinner Box” model is more subtile than that. This model uses partial reinforcement to compel a subset of players to spend in the game. Sometimes this is limiting the amount of time one can play the game, often tied to a value resembling ‘energy’, where the player expends energy to play and if they run out they need to wait a day before continuing. An in-app purchase allows them to buy more energy if they want to continue to play without delay.

However F2P is the dominant economic model for mobile games. More than 80% of mobile game revenue comes from F2P although much of that is in-game advertising (typically there’s an in-game purchase option to turn off ads).

It wasn’t always this way. Here’s an ad for game I designed and produced in 1982:

Avalon Hill — Controller

However as nostalgic as I am for the days when I could write a game in a few weeks and see it sold for what today would be $97.10 the fact is that F2P mobile games expanded the market greatly. Look at this chart for game revenue:

Mobile and as much as I don’t love it, F2P made gaming a mass market. Just take a airline trip and observe the wide demographics of the passengers playing games on their phones.

There are a huge number of mobile gamers. During the COVID lockdown of 2021, it reached 1.8 Billion. That’s almost 23% of the world’s 7.9 Billion people in 2021.

It’s a global phenomena driven in large part by the F2P economics.

As an independent developer of games there are some realities of the mobile game market that need to be acknowledged.

First off, if you’re advertising for players, what is the advertisng cost to get a player to install (download) your game.

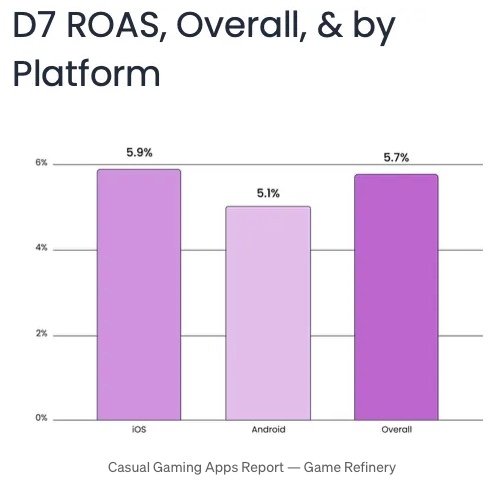

And here is the “Return On Ad Spend” by platform:

This implies that, on average, if you were to spend $1000 on an iOS ad campaign, you would hope to see $1059 in revenue.

This is a FALSE assumption for most developers. Here’s why:

A statistician had one foot in a bucket of ice water and one foot in a bucket of boiling water. He said, “My feet feel great, on the average.”

This is an industry wide average. The average is biased by the most successful games which dominate the revenue for casual mobile games. Advertising is based on a bidding model so the most successful games, the ones with the highest revenue, are driving the cost of acquiring players. So unless you’re as good as extracting cash from those 2% to 5% who are spending, as Candy Crush is, advertising spend will be a losing proposition.

So what does this have to do with web based games?

One major reason F2P won out as the dominate model for casual mobile games is simply this, it allowed you to experience the game without any financial commitment. You get to experience the game and if you find it to be worthwhile, then you can (optionally) spend some money on the game.

Yes, often F2P is more complex than that. There’s “pay to win” where you can make in-app purchases to gain an advantage in multiplayer titles, not something I’m fond of. On a lighter side there’s digital content, for example a hat for your character. But for this discussion let’s limit the F2P case where spending allows you to play more or unlocks additional game features.

So imagine you have a web version of a mobile game, IDENTICAL in look and play. You see a bit of this with playable ads, sadly many of those are misleading and don’t represent the actual mobile game, but the “try before you buy” model makes sense.

So you have your web based game, it is a facsimile of the game in the mobile app stores, and it allows you to play a portion of the mobile game. If you find the experience to be worthwhile you simply push a button and buy the App Store version that features unlimited play.

So what’s the catch? Discovery!

The Vikings ‘discovered’ the new world 500 years before Columbus

“If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

The App Stores, for all their issues, enable the discovery of games via search, app features (where Apple/Google decide to feature an app), rankings by download numbers, and advertising in the app store itself.

So how do you drive users to a web app?

Marketing starts with the decision to do the game in the first place. You need to plot out a strategy to get traffic to the web game.

There are several strategies here.

You come up with a topical game that gets media coverage. The issue here is that if you were to pick something political or humorous, you could face rejection from the app stores for your mobile versions. At that point you would need to add in-app purchases to the web game, possible but perhaps not popular.

Launch the HTML game on a platform that supports that. This could be Telegram, TikTok, Crazy Games, and others. You’re still faced with the discovery issue.

Co-Promotion with an existing website that has user traffic. The key here is that the web game has to relate to the website’s purpose, add value to the website, and most likely you’ll have to negociate a partnership with revenue share from the mobile apps.

I personally picked #3. In my case I had a real time movie trivia game, there are movie review sites with decent traffic and some even have web-based movie trivia games. I managed to strike a deal with one of the most popular ones who’s competitors already had a traditional movie trivia game.

So we’ll see how that works out in a follow up article.